LOS ANGELES – “You got a choice to make, man. You could go straight on to heaven. Or you could turn right, into that.”

We are in Los Angeles, in the heart of one of America’s wealthiest cities, and General Dogon, dressed in black, is our tour guide. Alongside him strolls another tall man, grey-haired and sprucely decked out in jeans and suit jacket. Professor Philip Alston is an Australian academic with a formal title: UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights.

General Dogon, himself a veteran of these Skid Row streets, strides along, stepping over a dead rat without comment and skirting round a body wrapped in a worn orange blanket lying on the sidewalk.

The two men carry on for block after block after block of tatty tents and improvised tarpaulin shelters. Men and women are gathered outside the structures, squatting or sleeping, some in groups, most alone like extras in a low-budget dystopian movie.

We come to an intersection, which is when General Dogon stops and presents his guest with the choice. He points straight ahead to the end of the street, where the glistening skyscrapers of downtown LA rise up in a promise of divine riches.

Heaven.

Then he turns to the right, revealing the “black power” tattoo on his neck, and leads our gaze back into Skid Row bang in the center of LA’s downtown. That way lies 50 blocks of concentrated human humiliation. A nightmare in plain view, in the city of dreams.

The tour comes at a critical moment for America and the world. It began on the day that Republicans in the U.S. Senate voted for sweeping tax cuts that will deliver a bonanza for the super wealthy while in time raising taxes on many lower-income families. The changes will exacerbate wealth inequality that is already the most extreme in any industrialized nation, with three men – Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Warren Buffet – owning as much as half of the entire American people.

A few days into the UN visit, Republican leaders took a giant leap further. They announced plans to slash key social programs in what amounts to an assault on the already threadbare welfare state.

“Look up! Look at those banks, the cranes, the luxury condos going up,” exclaimed General Dogon, who used to be homeless on Skid Row and now works as a local activist with Lacan. “Down here, there’s nothing. You see the tents back to back, there’s no place for folks to go.”

California made a suitable starting point for the UN visit. It epitomizes both the vast wealth generated in the tech boom for the 0.001%, and the resulting surge in housing costs that has sent homelessness soaring. Los Angeles, the city with by far the largest population of street dwellers in the country, is grappling with crisis numbers that increased 25% this past year to 55,000.

The richest 1% now own a staggering portion of the world's wealth

She receives no formal income, and what she makes on recycling bottles and cans is no way enough to afford the average rents of $1,400 a month for a tiny one-bedroom. A friend brings her food every couple of days, the rest of the time she relies on nearby missions.

She cried twice in the course of our short conversation, once when she recalled how her infant son was taken from her arms by social workers because of her drug habit (he is now 14; she has never seen him again). The second time was when she alluded to the sexual abuse that set her as a child on the path toward drugs and homelessness.

Given all that, it’s remarkable how positive Finley remains. What does she think of the American Dream, the idea that everyone can make it if they try hard enough? She replies instantly: “I know I’m going to make it.”

A 41-year-old woman living on the sidewalk in Skid Row going to make it?

“Sure I will, so long as I keep the faith.”

What does “making it” mean to her?

“I want to be a writer, a poet, an entrepreneur, a therapist.”

Robert Chambers occupies the next patch of sidewalk along from Finley’s. He’s created an area around his tent out of wooden pallets, what passes in Skid Row for a cottage garden.

He has a sign up saying "Homeless Writers Coalition," the name of a group he runs to give homeless people dignity against what he calls the “animalistic” aspects of their lives. He’s referring not least to the lack of public bathrooms that forces people to relieve themselves on the streets.

LA authorities have promised to provide more access to toilets, a critical issue given the deadly outbreak of Hepatitis A that began in San Diego and is spreading on the West Coast claiming 21 lives mainly through lack of sanitation in homeless encampments. At night local parks and amenities are closed specifically to keep homeless people out.

Skid Row has had the use of nine toilets at night for 1,800 street-faring people. That’s a ratio well below that mandated by the UN in its camps for Syrian refugees.

“It’s inhuman actually, and eventually in the end you will acquire animalistic psychology,” Chambers said.

He has been living on the streets for almost a year, having violated his parole terms for drug possession and in turn being turfed out of his low-cost apartment. There’s no help for him now, he said, no question of “making it”.

“The safety net? It has too many holes in it for me.”

Of all the people who crossed paths with the UN monitor, Chambers was the most dismissive of the American Dream. “People don’t realize – it’s never getting better, there’s no recovery for people like us. I’m 67, I have a heart condition, I shouldn’t be out here. I might not be too much longer."

That was a lot of bad karma to absorb on day one, and it rattled even as seasoned a student of hardship as Alston. As UN special rapporteur, he’s reported on dire poverty and its impact on human rights in Saudi Arabia and China among other places. But Skid Row?

“I was feeling pretty depressed,” he told the Guardian later. “The endless drumbeat of horror stories. At a certain point you do wonder what can anyone do about this, let alone me.”

And then he took a flight up to San Francisco, to the Tenderloin district where homeless people congregate, and walked into St Boniface church.

What he saw there was an analgesic for his soul.

San Francisco, California

About 70 homeless people were quietly sleeping in pews at the back of the church, as they are allowed to do every weekday morning, with worshippers praying harmoniously in front of them. The church welcomes them in as part of the Catholic concept of extending the helping hand.

“I found the church surprisingly uplifting,” Alston said. “It was such a simple scene and such an obvious idea. It struck me – Christianity, what the hell is it about if it’s not this?”

It was a rare drop of altruism on the West Coast, competing against a sea of hostility. More than 500 anti-homeless laws have been passed in Californian cities in recent years. At a federal level, Ben Carson, the neurosurgeon who Donald Trump appointed U.S. housing secretary, is decimating government spending on affordable housing.

Perhaps the most telling detail: apart from St Boniface and its sister church, no other place of worship in San Francisco welcomes homeless people. In fact, many have begun, even at this season of goodwill, to lock their doors to all comers simply so as to exclude homeless people.

As Tiny Gray-Garcia, herself on the streets, described it to Alston, there is a prevailing attitude that she and her peers have to contend with every day. She called it the "violence of looking away."

That cruel streak – the violence of looking away – has been a feature of American life since the nation’s founding. The casting off the yoke of overweening government (the British monarchy) came to be equated in the minds of many Americans with states’ rights and the individualistic idea of making it on your own – a view that is fine for those fortunate enough to do so, less happy if you’re born on the wrong side of the tracks.

Countering that has been the conviction that society must protect its own against the vagaries of hunger or unemployment that informed Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Great Society of Lyndon Johnson. But in recent times the prevailing winds have blown strongly in the “you’re on your own, buddy” direction. Ronald Reagan set the trend with his 1980s tax cuts, followed by Bill Clinton, whose 1996 decision to scrap welfare payments for low-income families is still punishing millions of Americans.

The cumulative attack has left struggling families, including the 15 million children who are officially in poverty, with dramatically less support than in any other industrialized economy. Now they face perhaps the greatest threat of all.

As Alston himself has written in an essay on Trump’s populism and the aggressive challenge it poses to human rights: “These are extraordinarily dangerous times. Almost anything seems possible.”

Lowndes County, Alabama

Trump’s undermining of human rights, combined with the Republican threat to pare back welfare programs next year in order to pay for some of the tax cuts for the rich they are rushing through Congress, will hurt African Americans disproportionately.

Black people are 13% of the U.S. population, but 23% of those officially in poverty and 39% of the homeless.

The racial element of America’s poverty crisis is seen nowhere more clearly than in the Deep South, where the open wounds of slavery continue to bleed. The UN special rapporteur chose as his next stop the “Black Belt,” the term that originally referred to the rich dark soil that exists in a band across Alabama but over time came to describe its majority African American population.

The link between soil type and demographics was not coincidental. Cotton was found to thrive in this fertile land, and that in turn spawned a trade in slaves to pick the crop. Their descendants still live in the Black Belt, still mired in poverty among the worst in the union.

You can trace the history of America’s shame, from slave times to the present day, in a set of simple graphs. The first shows the cotton-friendly soil of the Black Belt, then the slave population, followed by modern black residence and today’s extreme poverty – they all occupy the exact same half-moon across Alabama.

There are numerous ways you could parse the present parlous state of Alabama’s black community. Perhaps the starkest is the fact that in the Black Belt so many families still have no access to sanitation. Thousands of people continue to live among open sewers of the sort normally associated with the developing world.

The crisis was revealed by the Guardian earlier this year to have led to an ongoing endemic of hookworm, an intestinal parasite that is transmitted through human waste. It is found in Africa and South Asia, but had been assumed eradicated in the U.S. years ago.

Yet here the worm still is, sucking the blood of poor people, in the home state of Trump’s U.S. attorney general Jeff Sessions.

A disease of the developing world thriving in the world’s richest country.

The open sewerage problem is especially acute in Lowndes County, a majority black community that was an epicenter of the civil rights movement having been the setting of Martin Luther King’s Selma to Montgomery voting rights march in 1965.

Despite its proud history, Catherine Flowers estimates that 70% of households in the area either “straight pipe” their waste directly onto open ground, or have defective septic tanks incapable of dealing with heavy rains.

When her group, Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise (Acre), pressed local authorities to do something about it, officials invested $6 million in extending waste treatment systems to primarily white-owned businesses while bypassing overwhelmingly black households.

“That’s a glaring example of injustice,” Flowers said. “People who cannot afford their own systems are left to their own devices while businesses who do have the money are given public services.”

Walter, a Lowndes County resident who asked not to give his last name for fear that his water supply would be cut off as a reprisal for speaking out, lives with the daily consequences of such public neglect. “You get a good hard rain and it backs up into the house.”

That’s a polite way of saying that sewerage gurgles up into his kitchen sink, hand basin and bath, filling the house with a sickly-sweet stench.

Given these circumstances, what does he think of the ideology that anyone can make it if they try?

“I suppose they could if they had the chance,” Walter said. He paused, then added: “Folks aren’t given the chance.”

Had he been born white, would his sewerage problems have been fixed by now?

After another pause, he said: “Not being racist, but yeah, they would.”

Round the back of Walter’s house the true iniquity of the situation reveals itself. The yard is laced with small channels running from neighboring houses along which dark liquid flows. It congregates in viscous pools directly underneath the mobile home in which Walter’s son, daughter-in-law and 16-year-old granddaughter live.

It is the ultimate image of the lot of Alabama’s impoverished rural black community. As American citizens they are as fully entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It’s just that they are surrounded by pools of excrement.

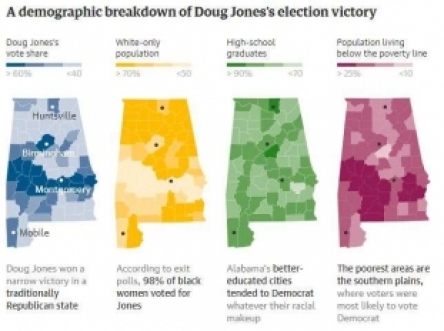

This week, the Black Belt bit back. On Tuesday a new line was added to that simple graphic, showing exactly the same half-moon across Alabama except this time it was not black but blue.

M/s Ressy Finley, lives in a tent on the 6th Street in downtown LA

M/s Ressy Finley, lives in a tent on the 6th Street in downtown LA The Black American citizen suffering it out on an outdoor bench

The Black American citizen suffering it out on an outdoor bench

Make A Comment

Comments (0)